The Goldilocks of the Elements: Why Iron Levels Have to Be ‘Just Right’

Without iron, there wouldn’t be life as we know it. The element is an essential part of the biologic operating manual for organisms from single-celled bacteria up to complex human beings. But iron also has a dark side: Because of its capacity to turn molecules into free radicals that can damage cell membranes and DNA, too much iron can be as dangerous as too little.

In the right amounts, iron is as important as the air we breathe. That’s because the element plays a crucial role in moving oxygen around our body after it enters our lungs.

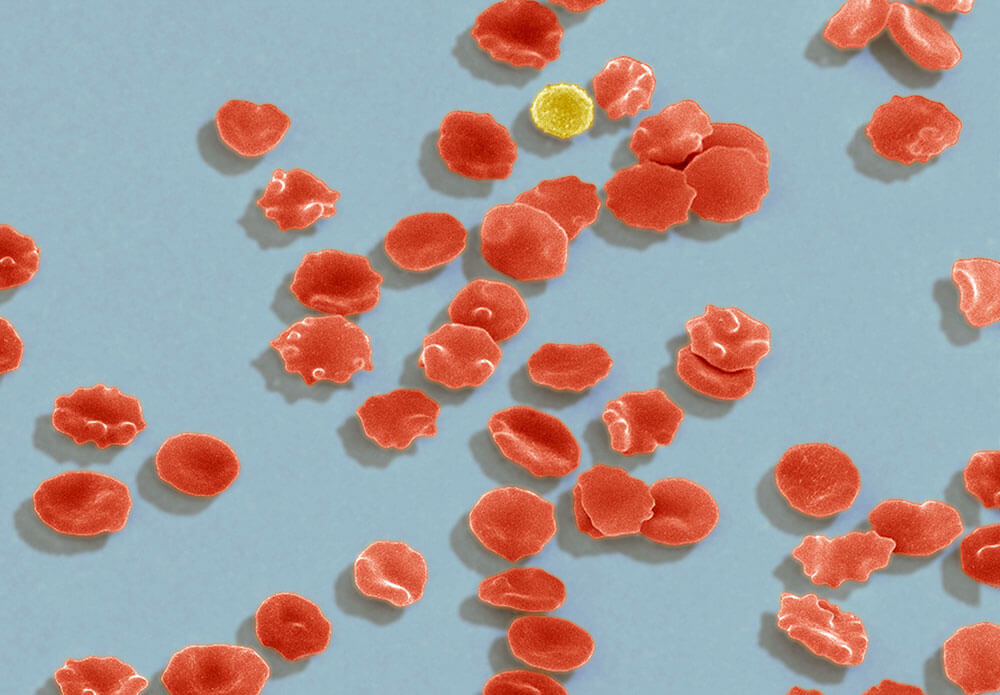

“If iron metabolism is working the way it should be, almost three quarters of the iron in a person’s body's is found in either red blood cells called hemoglobin or in muscle cells called myoglobin,” says Reema Jasuja, a Principal Scientist in Pfizer’s Rare Disease Research Unit in Kendall Square, Mass.

Both substances help us use or store the oxygen we breathe in through our lungs. Hemoglobin takes oxygen from the lungs to other tissues via the bloodstream. Myoglobin accepts, stores, transports and releases oxygen in muscle tissue. Both hemoglobin and myoglobin help sequester iron, letting it be useful while keeping it from damaging cells.

Perfecting the Balancing Act

Millennia of evolution have taught the human body to value iron, and it hoards the substance accordingly. In fact, the iron in hemoglobin is recycled when the body takes these cells out of service and replaces them with new red blood cells. The body’s hoarding of iron makes sense. Too little, and a person will suffer from anemia, a lowered ability to carry oxygen in the blood. Classic symptoms of anemia include fatigue and shortness of breath, exactly what you would expect when a person can’t effectively transport oxygen throughout their body.

But the body’s desire to hold onto iron means that it can sometimes accumulate too much of the element. In people who absorb more iron than average, the excess eventually overwhelms the body’s ability to safely sequester it. The result of all this rogue iron can be severe, leading to arthritis, cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes and heart problems.

Perfecting the balancing act necessary to keep iron levels just right is a serious engineering challenge for the human body. Fortunately, most of the time the body pulls off the feat incredibly well. However, genetic mutations or other abnormalities sometimes cause the amount of iron in the body to reach dangerously high or low levels. And in some cases a person can have both too much free iron in their body yet simultaneously suffer from anemia.

The Case for Efficiency

How is this possible? It has to do with abnormalities that keep the body from making effective use of iron.

“What you want is efficient use of iron to make red blood cells,” says Jasuja. “In the case of some genetic diseases, you have iron overload in tissue and anemia at the same time because the iron in the tissue can’t be used efficiently to make red blood cells.”

An example of an ailment that causes people to have both anemia and excess iron is thalassemia, a group of hereditary diseases characterized by faulty hemoglobin synthesis. Individuals who have severe cases of thalassemia not only make an abnormal form of hemoglobin that leads the body to destroy these red blood cells, but they also absorb more iron through their intestines, making them more susceptible to iron overload.

Scientists like Jasuja are currently testing promising treatments for conditions where an inefficient use of iron can lead to anemia and iron overload. If their work is successful, these conditions could someday be a thing of the past. For now, however, they are a stark reminder of the balancing act our bodies must undertake to keep iron working for us – not against us.